The Morphology of National Parliaments

Democratic Architecture;

This research into the history of democratic Architecture focuses on the morphology of national parliaments in the western tradition.

Democratic Power

The ideas of contemporary democratic ideals are based around the concept that free wo/men elect representatives that then meet in assemblies and make decisions for the good of the people. These meetings would take place in a democratic space with its own architecture. There are exceptions to this where direct democracy side steps representation, the best modern examples for this are the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus, or the Power of Referendums in some of the United States of America. The following research focuses on the formal approaches to representative democracy, direct democracy and its spatial ideals would be a subject of another study.

The space that democratic assemblies meet in, the parliament or assembly has a long and diverse architectural history. Contemporary parliaments are purpose built structures and their design is influenced by historical, philosophical and often cultural factors. The geometrical design of these spaces shape and influence the modes of democratic function like no other architecture. The use and perception of these spaces also reflects the evolution of political thought and current agendas. The morphology of debating chambers often carry anecdotal history and/or are assumed to be a direct decent of Greco-Roman democratic Senatorial Debating Chamber architecture. This lineage is often based on wistful thinking and forgotten history as the following text will argue.

In the modern emergence of liberal democracy, there needs to be a debate of whether the Greco-Roman Senate archetypes are an apt guide to contemporary assemblies.

Architecture of a Civil War

“They were once ruled by kings, but are now divided under chieftains into factions and parties. Our greatest advantage in coping with tribes so powerful is that they do not act in concert.” Tacitus.

The contemporary democratic state has its direct origin in the English Civil War, its debates, theories and attempts at a republican nation state. The English Commonwealth did not produce any significant democratic architecture or state building itself, but did mark a period between the Middle Ages and the enlightenment, between late renaissance classicism of Inigo Jones (1573-1652) in England and the new Baroque of Christopher Wren. The war was a conflict between an established and evolving Parliament and the monarchy. This establishment and the continuing conflict between the royalists and parliamentarians meant that no viable Republican architectural style was created. The change in styles from the Classical to Baroque owes more to the royalist exiles at the French court than any new science-based democratic architecture. This is true for the debating chamber of the Parliament too.

Before, during and after the Civil War Parliament met in the Old Palace of Westminster, in rectangular space dedicated to the purpose. The seating arrangement had the King, his representative, or during the Civil War, the Speaker of the House sitting at one end, facing the entrance, and the parliamentarians sitting along each long side facing each other. (Fig.1)

Re-birth of democracy

Fig 1. Houses Of Parliament 1640 English School

It wasn’t until the next civil war under the English crown; the American Revolution that a new radical ideal of democratic architecture was established. The Revolution was without a doubt a direct evolution of the ideas and principles of the English Civil War, including the Putney Debates and Thomas Hobbes. The ideas of the Civil War easily caught on in the independent thinking colonies. Many of the post Restoration colonials were also decedents of “radical” republicans of the Civil War who sought new opportunities in the New World. The ideals of the Civil War would also have a profound influence on the founding of the new Republic, the most prominent political theorist being John Locke (1632 – 1704). (Kohen, Lunsford 2009)

The New World democracy

At the time of the Revolution neoclassicism was becoming dominant in Europe. based on a more precise study of the Greek and Roman architecture. This became identified with the democratic values of the new republic in the United States and dominating as the democratic architecture of the new world. The founders perceived themselves as the inheritors of the ancient democracy of the Roman Republic, both in terms of philosophy but also significantly as a no less hereditary rulers than monarchs. (Crick 2002). The “new” democratic architecture was therefore also infused with a level of power.

Germanic Origin of Democratic Assemblies

However the heritage of the English democracy has much less to do with the Mediterranean democracies and much more with the Germanic ones. The tradition of a council of assistance and advice can be traced back to the Whitenagemot (the meeting of wise men) which was an Anglo-Saxon advisory council to the King.

Fig 2. Whitenagemot as illustrated in the Hexateuch (11th-century)

Whitenagemot

These assemblies dealt with jurisprudence and taxation but could also elect and dethrone a King. The Whitenagemot were a monarchical evolution of the traditional Germanic “Thing”, called Folkmoot in England. These were much more decentralized power-bases and functioned as an assembly of the community leaders. These would presumably meet in external spaces with their own democratic spatial architectural tradition.

The oldest survivors of such assemblies are the the Tynwald of the Isle of Man, Althingi in Iceland ant the Logting of the Faeroes Islands, all with their specific tradition of democratic architecture.

The Normans

With the Norman (again, northern Germanic) invasion of England in 1066, William I replaced the Whitenagemot with a less powerful advisory body called Curia Regis (directly translated as the Kings Court). Not only was this less powerful, but the members were now only those holding lands directly from the King. The Monarchy therefore held the assembly under complete control, only seeking it´s advise when needed. Henry I (1068 – 1135) was forced to reestablished some of the right and limits of the Kings power with the “Charter of Liberty” in 1100. This power struggle between the representative assembly and the monarchy has continued to this day with a direct influence on the British “democratic” architecture or the Parliament debating chambers.

The Basques

One can speculate that the history of democratic politics in Britain goes even further than the conquest of the Anglo-Saxons. Britons are genetically related to the Basque people of northern Spain and south-western France. The Basques were historically known for the equality of the sexes and for democratic forms of governance. Some of which survived until medieval times as Elizate, an early form of local government where the family heads would meet in front of the local church to decide on local matters. Tacitus´s description of the Celtic Britons above also indicates a form of decentralization. But this must remain a speculation. Again the democratic space would be the architecture of a local convenient landscape.

Descendant

So what is the architectural inheritance of this democratic heritage? There is no doubt that the formal or informal seating arrangement, itself forming a body of space, a space of bodies, is important in the power organisation of the assembly. It is the most primitive of human social organisation, who sits where, who speaks, where the focus is.

Fig 3. Germanic Thing, drawn after the depiction in a relief of the Column of Marcus Aurelius (AD 193)

The early Thing and Folkmoot meetings were held outside, often in fields as indicated in the numerous Thingvellir/Thynwald names for the meeting places. The column of Marcus Aurelius shows a stylized image of one such meeting.

Although difficult to decipher, one can attempt to project the spatial organisation from it and compare this with the historical records of the Icelandic Althingi, a Thing that survived well into late medieval times. The democratic architecture has participants face each-other and there is a place of oratory to one side. The status of the role of the Law-sayer (who recites the country law from memory) supports this. The Column of Marcus Aurelius indicates a progressively raised platforms for the members. This is supported by the Isle of Man´s Tynwald Hill arrangement and the Logberg (law rock) In Thingvellir, Iceland. This arrangement is the reverse of the typical amphitheater arrangement of the Greco-Roman senate. There the seating arrangement is concave, with participants sitting in an amphitheatre style seating looking down towards the speaker. In the Germanic Thing the participants sit in a convex seating arrangement with the most powerful sitting at the top. There the participants sit above and face the general public in attendance.

Fig 4. Isle of Man´s Tynwald Hill

Fig 5. Logretta, the place of the Commonwealth Assembly, Thingvellir, Iceland, Illustration.

This is a very different type of democratic architectural morphology. We could argue that the amphitheatre style is one of elitist, as the chamber is inward looking, used for and by the selected assembly only. The Germanic convex style is much more egalitarian, where the representatives, with their arguments and views, are on show to the public. These regional and national assemblies occurred periodically (usually annually) and the attendants would erect temporary accommodation adjacent to the assembly itself. These assemblies therefore became equally important meeting and market places between the various areas of the region. The democratic organisation and architecture hierarchy of this temporal nomadic town was no less important than the organisation of the assembly itself and would benefit from further study.

Inherited monarchy

Fig 6. The Bayeux Tapestry

The organisation of these assemblies would dramatically change with the onset and increasing power of an inherited monarchy. The original assembly places became redundant when the power sat with the monarch, wherever the monarch sat. And while the elevation of the assembly, both gave it status and made it visible (and accountable) to the general public, now the elevated position was conceptually and physically with the sole ruler, the monarchs on his throne.

This change also affected the seating arrangement of the assembly itself. The Royal Courts would vary in size and purpose, but there are some common features. The Monarch (and the throne) would be a central or a focus feature (as literally demonstrated in the Bayeux Tapestry).

Architecture of Power

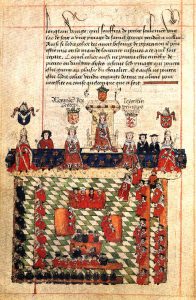

Fig 7. Edward I presiding over parliament in c.1278, from the Garter Book c.1524.

Fig 8. Estates-General convened in Versailles, France on 5 May 1789.

In larger assemblies the Court would sit in front of the Monarch who would sit on a throne, a seat on a raised platform at the end of the hall opposite the entrance, a typical arrangement common in manors in medieval Europe. The raised platform resembling the former Thing arrangement. On the Monarchs side would sit his most trusted advisors and family facing whomever presents his or her case to the Monarch. This is a clear arrangement of power, with the person facing the monarch both lower level and with the back to a more exposed and less formal side of the space. On either side of the main space the members of the assembly sit opposite each-other. Whether this was originally done on purpose or not one would have to speculate, but this again offers the monarch a position of power. The arrangement is a confrontational one, encouraging a two sides to debate with the monarch physically outside the confrontation, while at the same time dominating the session below. A power above and beyond any confrontation to itself. This arrangement, the arrangement of confrontation is still the democratic architecture of the current Houses of Parliament in Britain and many of the Commonwealth countries.

Fig. 9 The last Curia, built by Diocletian in 412AD

Imperial Rome

The Imperial Roman Senate followed the same principle of a confrontational arrangement, with the Presiding Magistrate sitting at the prominent end, and Senators facing each other over the aisle. Just like the British system, seating was arranged according to the power of the Senator, with the most powerful lowest and closest to the aisle.

The Roman Curia (Senate) as well as similar arrangements for royal courts in Europe dispel the idea that the parallel confrontational debating arrangement of the British Parliament originated from the time that the house of commons was given a permanent place in St Stephen´s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster in 1548. The anecdote says that the Parliamentarians would sit in the quire pews of the chapel, facing each other with the altar at one end where the Speaker of the House would sit. Today the members bow to the Speaker as they would have to the altar. A democratic architecture by accident rather than thought. The more plausible explanation is a reverence to the Monarch.

God

There is of course no coincidence in many similarities between the architecture of a Royal Court and the Church. State power has always looked to ecclesiastical architecture for inspiration in how to project and manipulate power through design rather than democratic traditions. But there is another older tradition that could have influenced this arrangement. In Northern Germanic architecture the seating arrangement in longhouse feasting would follow similar arrangement. The longhouses had a long central hearth and seating was organised in facing rows on either side of the hearth. However, counter to the Roman or Royal Assembly, the most prominent seats were in the middle of the rows and the further away from the middle, the lower prominence the person had.

The Round Table

Despite this current and historic oligarchy running through British politics, the idea of equality and democratic liberty runs deep in the British psyche. No clearer than in the story of King Arthur and the round table. The Arthurian myth is an obvious allegory of a more egalitarian democracy where the round table is the democratic formal arrangement of the spatial architecture. The round seating is an arrangement of equality and dialogue over authority or two sided confrontation.

Continuing Royal power

It is no coincidence that the reconstruction of Westminster in 1840 retained both the name of the Palace of Westminster, and the symmetrical and formal shape of a Royal Palace. To this day state architecture is expressed with the morphology of both democratic architecture, and authoritative and elitist state.

The “overseas”

Other European democracies followed a similar historical trajectory as the English, first overtaking the palaces of the deposed monarchs, and later to emulate their architecture in new palaces. The democratic seats of European state´s power continued to be a palatial architecture until after the Second World War.

America

But what of the other inheritors of the Anglo-Saxon democracy; The United States? The founders agreed on a new capital for the nation in 1790 in what is now Washington D.C. Looking for inspiration in Classical architecture, the new democratic architecture style of the young Republic became a mixture of the formal approach of Neoclassicism with the simplicity of Georgian architecture. This new Federal Style used many of the ancient and modern form of power projection. The architecture was over-scaled and symmetrical. Humanism is small in scale and asymmetrical; authority is large scale and symmetrical reducing the individual to a powerless being in front of the state.

Power of scale

The use of scale to project power is as old as architecture. The ancient Greeks would build temples that imitated the same construction methods as domestic architecture, but over-scaled them, emphasised symmetry and transformed domestic readily available materials into more permanent stronger materials. Wood to stone. The access doors into the temple were oversized, and when worshipers entered the temple, an enormous statue of the god or goddess would face them down. This was not a house for humans, but the home of a God (al be it temporal). The gods did not rule as democratic beings, and neither did their architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright

This Greco-Roman approach to democratic architecture has been criticised by many, not least Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). Wright’s architecture was anti palatial, asymmetrical over symmetrical, and expressed the bond between the American individual and the natural land he/she lives on. His remark that “The Lincoln Memorial is related to the toga and the civilisation that wore it. “ was not compliment or a confirmation of the founders dreams of the new Roman Republic, but a reference to the Roman Empire (Crick 2002).

The two Chambers of Congress digress significantly from the English Parliament, following the geometrical example of the Greco amphitheatre, with the Speakers of the House on a raised dais in the centre, facing the assembly. It´s morphology is less confrontational than the British, but does retain some of the power projection of the senatorial leaders, as well as the elitism of the Greco-Roman design.

Fig 10. United States Chamber of Congress

Liberal Democracy

The American Republic that was founded in 1776 was not a Liberal Democracy as we know today. It was a compromise of ideas, in many ways based on the ideas of the Roman Republic, where power was balanced between the aristocracy (Senate) and the public (through the Tribunes). The United States Congress was separated into two houses in 1787 reflecting this ambition, and using the same arguments as the English did with the two Houses of Parliament. The US did not have universal suffrage; one had to be white (except in some Northern States), male and a landowner. This was not a modern democracy, but an Aristotelian one. The United States did not have Universal Suffrage until 1920, the United Kingdom not until 1928. Liberal Democracy is therefore a relatively modern idea that has grown out of republican forms of government. The early democratic architecture of the United States would therefore reflect this.

The architectural expression of this more recent liberal form of a democratic state is still evolving. Current solutions have their design principle origins in modernism, from the designs of The National Congress of Brazil by Oscar Niemeyer and the Bangladesh Parliament by Louis Kahn amongst others. These principles have been later developed in projects such as the Scottish Parliament by Enric Miralles and the new Reichstag by Norman Foster. The modern examples pay homage to the Greco Senate Amphitheatre organisation while aiming to represent the liberalisation of democratic principles. Many of these principles are now echoing the organisations of the old Germanic assemblies. Generally, these follow three principal paths:

Equality

Fig 11. The Welsh Assembly Building, Debate Chamber.

One is to equalise the power projection of the assembly members. Examples include removing the elevation of the “leader” of the assembly, (The Welsh Assembly Building by Richard Rogers), reduce the raking of the chamber seating etc.

Fraternity

Fig. 12 European parliament chamber

The second is to remove the confrontational nature of the old assemblies and create a colloquial oriented arrangement. This is done mainly through rounding out the chambers, removing any corners and thereby removing focal nodes and places of perceptive power.

Liberty

The third technique is to make the chambers familiar, close and informed to the public. This included avoiding the “palaces of power” architectural styles, but also making the chambers more accessible and visible to the public. Niemeyer made an obvious modernist geometrical (and highly symbolic) gesture in Brasilia, while in fact the interior of the Chambers are not visible from the outside. Later architects have attempted to open the chambers to the constituents, both visually and via access. These have sometimes lead to plays with power, where the audience are placed above and principal to the assembly members. (e.g. the German Parliament, the Reichstag by Norman Foster)

Fig 13. The Reichstag audience space

The future of democratic architecture

Looking at western parliaments today it becomes obvious that the post 9/11 Liberal Democracy is under siege, with security measures (hopefully) unintentionally creating a barrier between democratic representatives and the people they represent. This is a new parameter in the architectural morphology of liberal democracy.

Democracy is not unfamiliar with violence. Representative assemblies have gone to wars, in international conflicts as well as with internal separatism and terrorism. Is this something different? Perhaps it is. While past conflicts were between authoritarianism or alternative types of democracy the difference is not just that the enemy is fighting the very principles of democratic though, and will use any means necessary to destroy it.

The difference is also that Liberal Democracy itself is new, and has not had to face these kind of conflicts before. Whatever the answer is, this is a factor that now is unfortunately something that has to balance against the open and liberal design principles of Liberal Democracy.

References

Fig 14. The morphogenesis of democratic space

Tacitus: Agricola, C98, (De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae) Book 1.

Kohen, Ari. Lunsford Sara W. 2009 “American Revolution” pp. 52–56 Published in “Encyclopedia of Human Rights”, David P. Forsythe, Editor-in-Chief (Oxford), Oxford University Press.

Crick, Bernard, 2002 “Democracy; A Very Short Introduction” (Oxford). Oxford University Press,

H. G. Richardson, 1928. “The Origins of Parliament”. 11, pp 137-183. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (Fourth Series),

Pritchett, Virgil J. 1917-1918, “Origin and Growth of Parliamentary Government”, Kentucky USA, Kentucky Law Journal.

Rescher, Nicholas, 2009, “Free Will: A Philosophical Appraisal”. Transaction Publishers.

Raynaud, Philippe July 1993, “Philosophy and Democracy” Journal of Democracy, Volume 4, Number 3,

Pangle, Thomas” 1992, The Ennobling of Democracy: The Challenge of the Postmodern Age”. Johns Hopkins University Press, 227 pp.

Translated by William Rehg 1998, “Between Facts and Norms, Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy” MIT press, Retrieved from URL “http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/author/default.asp?aid=139” Jürgen Habermas) Aug 1, 2010

Icon Group International, 1 May 2009 “The British Parliament: Webster’s Timeline History, 1312 – 2007”, Publisher: ICON Group International, Inc.

Norton, Philip, 5 Aug 2005, “Parliament in British Politics” (Contemporary Political Studies) Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan; illustrated edition.

Cole, Matt, 3 April 2006 “Democracy in Britain” (Politics Study Guides), Publisher: Edinburgh University Press

Grant, Moyra, 21 Mar 2009, “The UK Parliament” (Politics Study Guides), Edinburgh University Press

Mayer, Annette, 5 April 1999, “The Growth of Democracy in Britain” (Access to History – Themes) Hodder Arnold H&S

Hemmings, Ray, 16 Oct 2000, “Liberty or Death: The Struggle for Democracy in Britain 1780-1830“, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd

List of Figures

Figure 1. Author Unknown (English School) Houses Of Parliament, 1640, Public Domain.

Figure 2. Cotton Claudius B. IV, f.59, Old English Illustrated Hexateuch, England; second quarter of 11th century, original at the British Library, image in Public Domain

Figure 3. Buch-Scan von Wolpertinger, Germanic Thing, Bibliothek des allgemeinen und praktischen Wissens, Bd. 2. – Berlin, Leipzig, Wien, Stuttgart: Deutsches Verlaghaus Bong & Co, 1904. – 1. Aufl.). Drawn after the depiction in a relief of the Column of Marcus Aurelius (AD 193) Public Domain.

Figure 4. Isle of Man´s Tynwald Hill, Tynwald Day (site) http://www.tynwald.org.im Public Domain.

Figure 5. Author Unknown, Lögretta, Thingvellir, Iceland. (site) www.thingvellir.is Public Domain.

Figure 6. King William´s court, The Bayeux Tapestry, Public Domain.

Figure 7. Edward I presiding over parliament in c.1278, from the Garter Book written and illustrated for Sir Thomas Wriothesley in c.1524. Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medieval_parliament_edward.Jpg Public Domain.

Figure 8. Estates-General convened in Versailles, France on 5 May 1789. Biblioteque Nationale de France; http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b69426650/ Public Domain.

Figure 9 Abernathy, Dean, The last Curia, built by Diocletian in 412AD, (Curia Iulia pavement, Roman Forum. ) 24 May 2008, Photo by Rodrigo Caballero R. Public Domain

Figure 10. Unknown employee of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, United States Chamber of Congress, State of the Union address, Jan. 28, 2003. Public Domain.

Figure 11. The Welsh Assembly Building, Debate Chamber. UKWiki, http://en.wikipedia.org, Public Domain.

Figure 12. CherryX; European Parliament, Plenar hall, March 2012, Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Attribution: ©2012 CherryX per Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:European_Parliament,_Plenar_hall.jpg Public Domain

Figure 13. The Reichstag audience space in the building dome, © Tuulum | Dreamstime Stock Photos & Stock Free Images, http://www.stockfreeimages.com

Figure 14. By the Author, The morphogenesis of democratic space, 2014

By Gudjon Thor Erlendsson

© 2014 Gudjon Thor Erlendsson, all rights reserved.