2019 context

London Housing Crisis and possible solutions

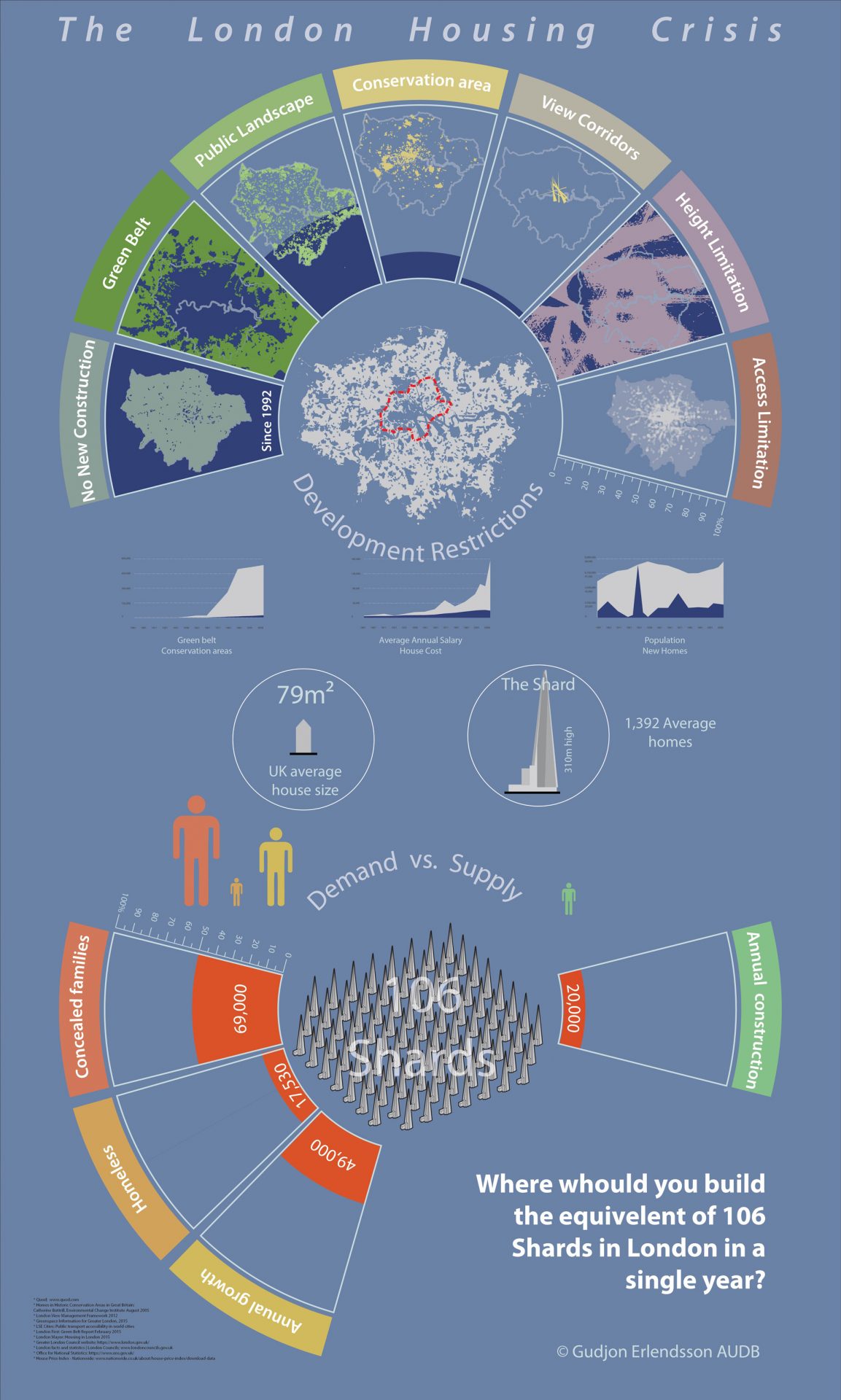

Urban planning is a strategic endeavor. It involves the maintenance and improvements of the existing and facilitation of growth, or reduction. It uses statistical tools to predict future needs and strategically plans for the urban accommodation of those needs. When these strategies are not met, Urban Planning is failing. The “housing crisis” in the UK is not a “natural” condition but rather demonstrates that urban planning in the country is a complete failure.

London needs the equivalent of 92 Shard skyscraper per year to accommodate it’s growth. The supply is nowhere near this quantity.

History

London, much like the UK in general, has a very chequered history when it comes to urban planning. The city has grown in largest extent either by organic means, or by the incremental and localised visions of developers. Urban planning set forth by a civil society has had very limited impact compared to other European capitals.

The Great Fire of London offered the city an opportunity to create a major visionary urban plan, but took too long to agree on a plan so the opportunity was squandered. In more modern times, the organisation that has had the greatest impact on urban development in London was the Luftwaffe during the second world war. After the war, bomb sites in London became the places of urban development filled with large scale construction in the modernist tradition.

A strategic bombing campaign is not a good urban development strategy, even if made by the the Luftwaffe. It is not a surprise that so many of these projects were a complete failure. Despite this bizarre planning strategy, some of these projects vastly surpassed their restrictions thanks to visionary architect.

Going forward

As discussed and summarized in “London; In Crisis” the UK planning system is not properly fit for the purpose of urban development. Rather it is a conservation driven bureaucratic system made to preserve the existing and shoehorning a 21 century needs into a 19th century form. The system is not just impractical, but has a significantly negative effect on economical performance. This is not a surprise to anyone, least of all city Councillors or Westminster MPs. Political strategists estimate that whichever party fixes this problem for good, will loose the next general election. The British are by design a conservative lot.

As demonstrated in the article, the planning system is the underlying reason for house prices and the “housing crisis”. Simply put, not enough is being built to meet demand.

Without fundamentally changing the system what are the paths to real solutions? There are a couple of alternative options; in essence policy or master-plan.

Policy

The planning “restriction” system creates the demand and price increase. This is essentially a hidden “tax” which transfers fortunes from those seek and need property (young people) to those that own property (older people). This hidden tax can be reversed and shared between the home owners that benefit from these amenities, and the home seekers who are disadvantaged by the system. This would be based on:

Tax:

A tax on the square foot of locally listed buildings and conservation areas, collected from local property owners. Collected by the metropolitan authority (GLA) and used to build affordable and social housing to counteract the development restrictions. This would mean e.g. that councils that use local conservation to restrict all development would contribute to the development of affordable housing in the wider areas of the city.

Design:

Often the rejection of development is not due to the adversity to development per-se, but the rejection of bad design. It can not be dismissed that allot of developments are poorly designed, focused on fast and cheap construction with little regard for quality or aesthetics. Unhelpfully the power of local planners has increased their confidence to direct design, which they are neither trained or appointed to do. Architects are experiencing local planners and conservation officers literally designing buildings within a ‘consultation’ period of planning applications. Planners and conservation officers see themselves more and more as “Architectural Police” rather than the facilitators of urban development. This is both lowering design standards, adding time and costs to new development and counter to solving the housing crisis.

A solution would be to offer an alternative planning direction based on design competitions and qualitative evaluation.

Competitions

One option would be for developers to submit their project to a design competition with minimum of 3 invited Architects which are then judged by a professional independent body of architects and representatives of the City or County. This could be organised by the Royal Institute of British Architects, perhaps based on the Swiss model. This model is where an Architects office is hired by the local authority to plan and execute the competition as an independent body. This option would then bypass the typical planning process directly to the “building control” phase”. This could both speed up and loosen up the gridlocked planning system while at the same time raise the design quality of the built environment. With larger scale projects in London taking 14 years to go through the planning system, this could be an apt alternative.

Masterplan

The second strategy in solving the housing crisis is a proactive planning in London. A policy based future development strategy, Including geo-strategic construction, mass transportation and infrastructure. Lateral to limited and realistic national and regional building conservation. dismissal of conservation area policies, with some strategic, but limited height restriction. In essence a pre-planned and visionary urban design for London.

Tactical options include:

- Allow each city block to build a tower that does not affect the building facades at ground level. Each tower would have to go through a competition with a minimum distance between towers. Meaning that the best design would dominate.

- Turn West London into a living “museum” a la Venice, and open the east to development with no conservation areas allowed, limited height restrictions within a unique independent London planning system outside national planning. All future public transport system growth would have to concentrate on the East, making the East into the new centre of London. The density and design would have to concentrate on walking and cycling to help minimise long commuting.

- New London; a new city build outside, but close to London. The either side of the Thames estuary is the ideal location with all finances for transport in London focused on the new city. The rest of London could then be turned into a “museum” as above. Again density and design would have to concentrate on walking and cycling

- North / South split with all of the South open for development and the north turned into a “museum”. Again all transportation would have to be diverted to the South.

- Centre development. No conservation allowed in the centre of the city, with the GLA controlling all development, focusing on high-rise. The density and design would have to concentrate on walking and cycling

- Network development: a proposal where the connectivity of each station on the transportation network would indicate the size of development allowed without restrictions around each station. Any local authority that does not meet the development mark, would to provide taxed funding to the development of other councils.

Conclusion

These are not exhaustive options or ideas for the solution to the housing crisis, but a way to open up a dialogue. With the planning system not fit for purpose, and need far outstripping development, this is the time for imagination and bravery in urban development in the City.

By Gudjon Thor Erlendsson

© 2017 Gudjon Thor Erlendsson, all rights reserved.