Competition

HRW Engineers

Vasile Buda

Heidar Thor Jonsson

Gudjon T. Erlendsson

Mehtap Altuğ

Wei-Ke Cheng

Ertunç Hünkar

Irem Cabbaroglu

Gabriel Pavlides

2018

Cultural Parametric

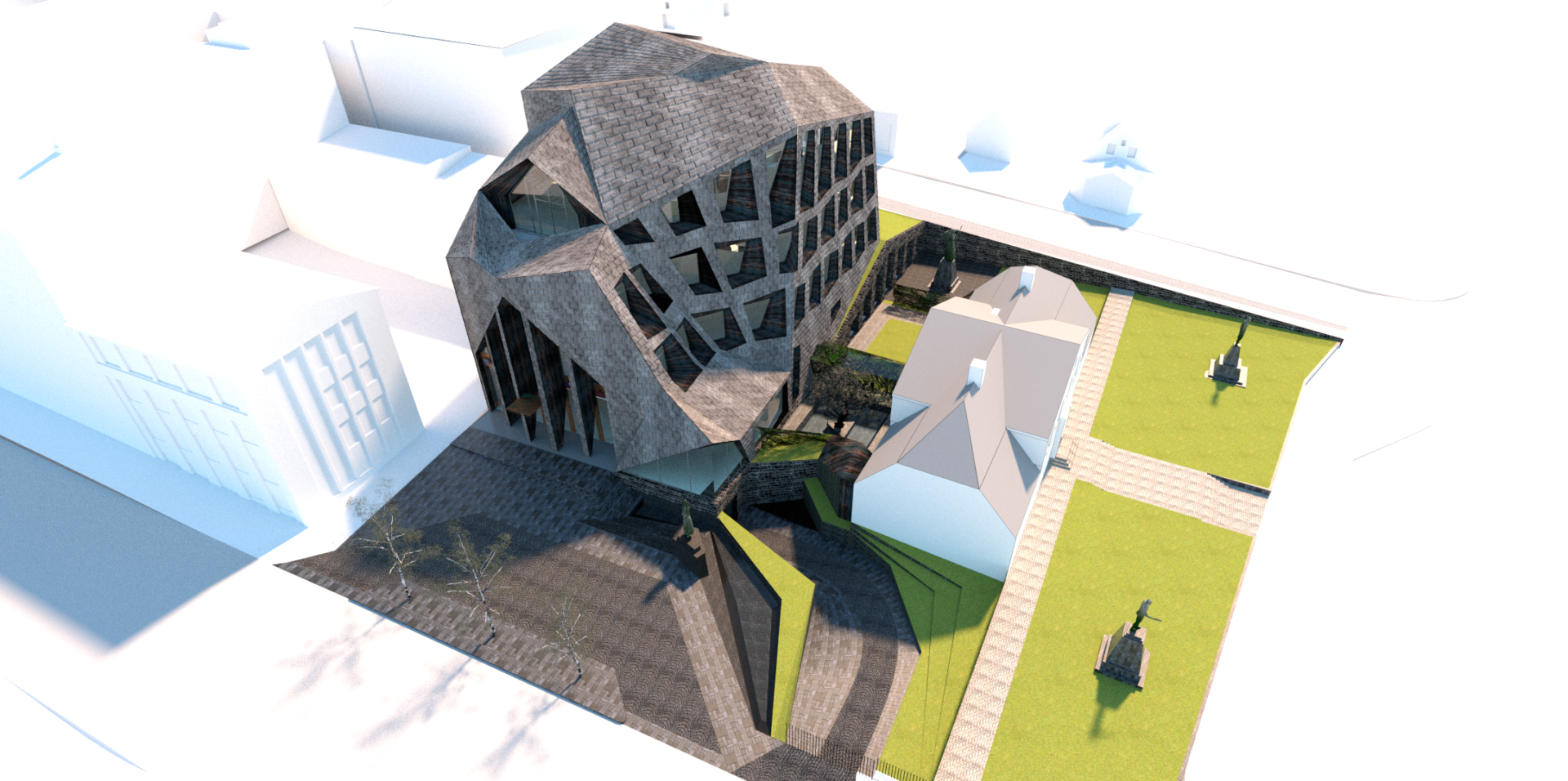

A new Parametric Vernacularism inspired by the historical Norse law-things held under the Logberg cliff; a landscape-building to the historical capital building of Iceland.

Aim

Competition Brief

The competition for the project was conceptually conceived in 2018 by the government of Iceland as an extension to their Stjornarradshus (Cabinet of Ministers Building).

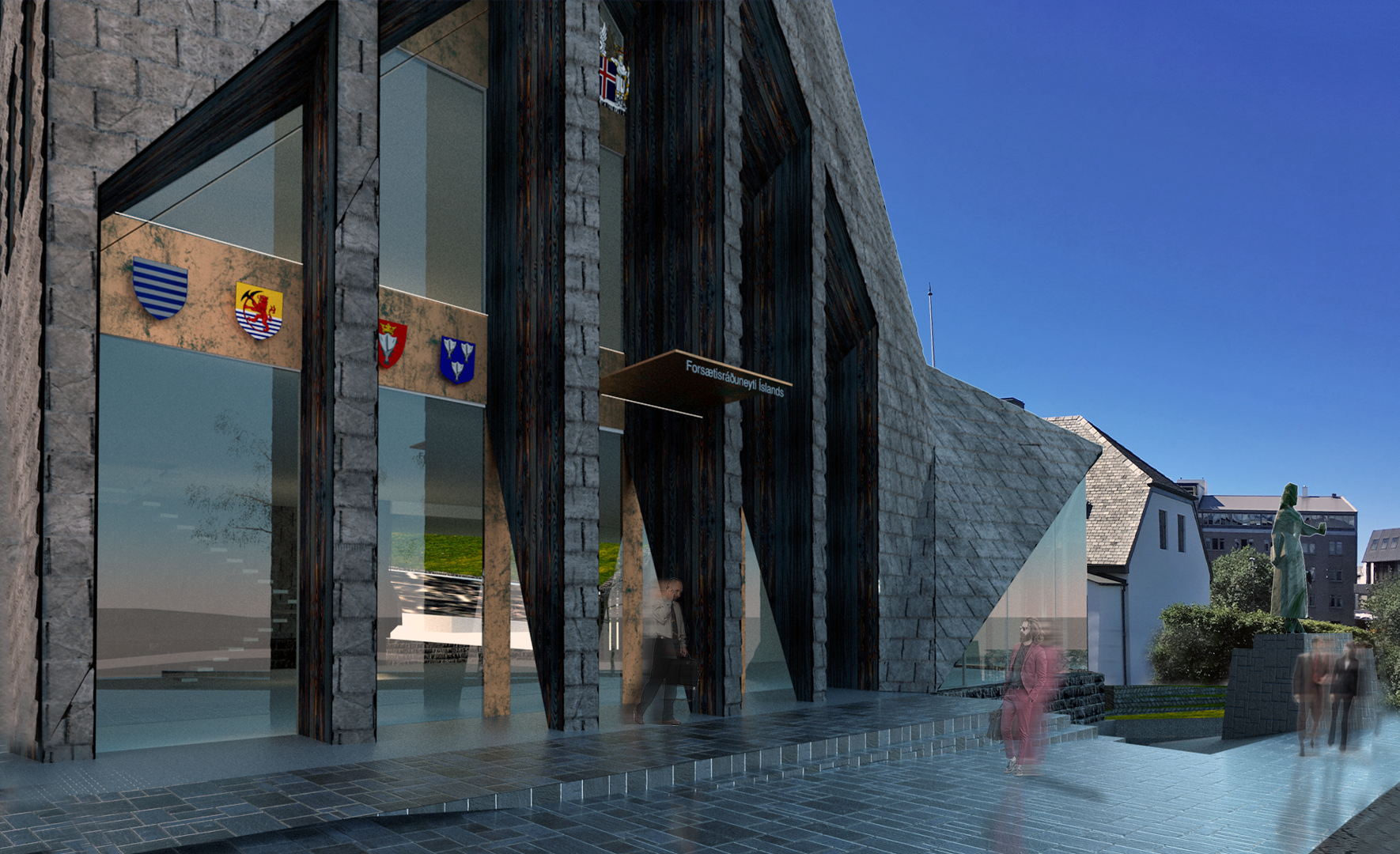

The aim was to collect currently dispersed offices of the Prime Ministry and Executive into a single location, while the design should aim to represent the Icelandic community and expresses society’s current ideals: justice, government transparency, sustainability and cultural sensitivity.

Rather than a completely new site, the decision was to build an extension to the existing Executive Building of Iceland creating a holistic solution for the site.

While the office worked closely the competition brief throughout the design development, the proposal was ultimately rejected by competition jury after six months of work.

Context

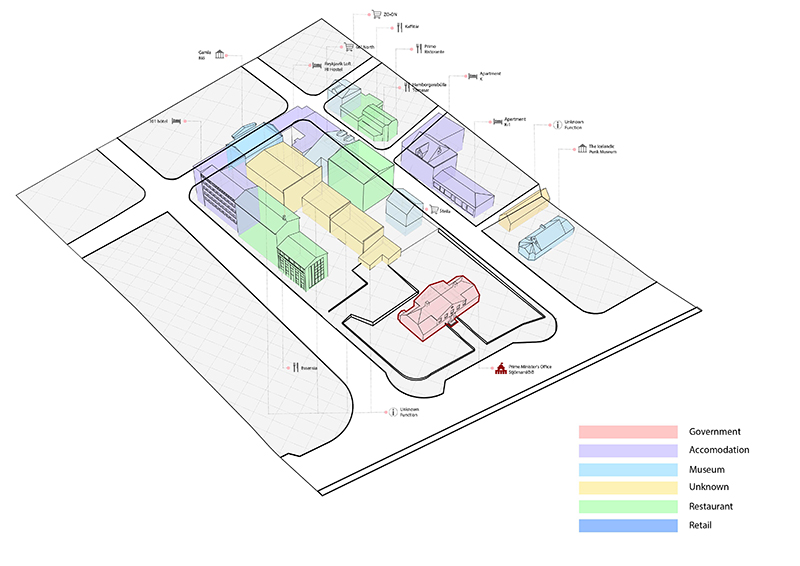

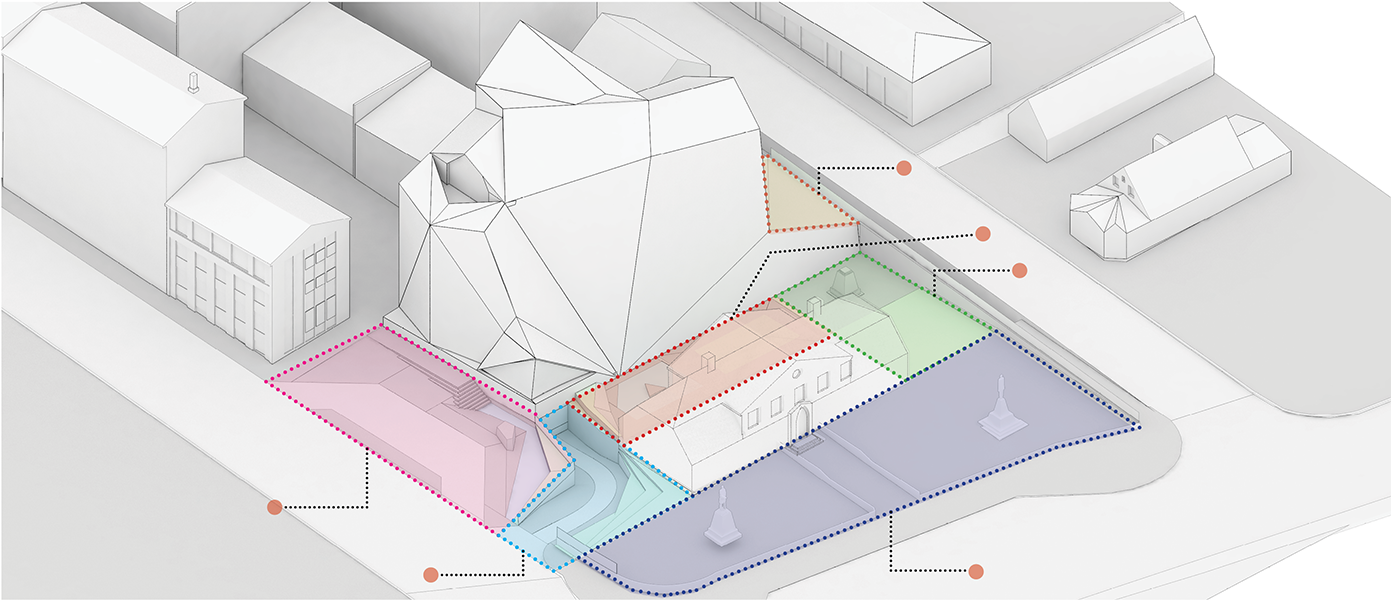

The Stjornarradshus (Cabinet of Ministers Building) is located in the historical centre of Reykjavik. The site sits on a slope overlooking the historical town centre with the Arnarhol public park to the north and Laugavegur shopping street traversing the slope to the south. The site for the new building is set at the rear garden on the historical building.

The site calls for a thoughtful scale and communication with the cityscape while showing sensitivity and consideration to the image, role and historical importance of the place especially the Stjornarradshus.

The important position of the Cabinet should maintain the street scene of Lækjargata that crosses the front of Stjornarradshus and to ensure unwanted appearance from important perspectives. While a new entrance was to be located off Hverfisgata to the north of the site. Emphasising the importance of the nation´s executive.

Space planning

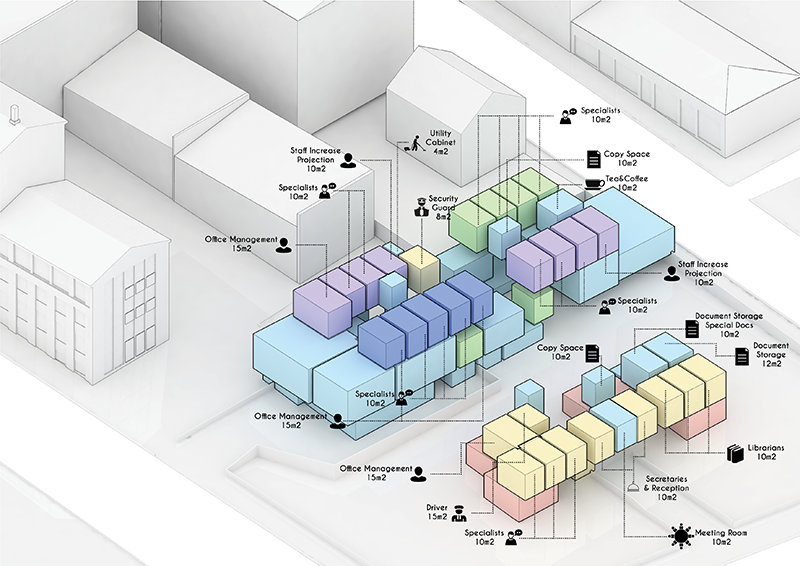

The new building incorporates essential new facilities to collect dispersed functions and meet the increasing demand for effective governmental activities. Providing a good working environment, flexibility in utilization and being affordable in operation.

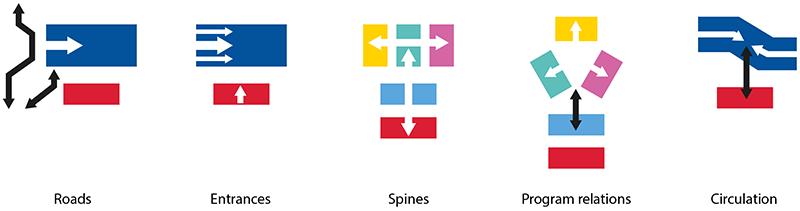

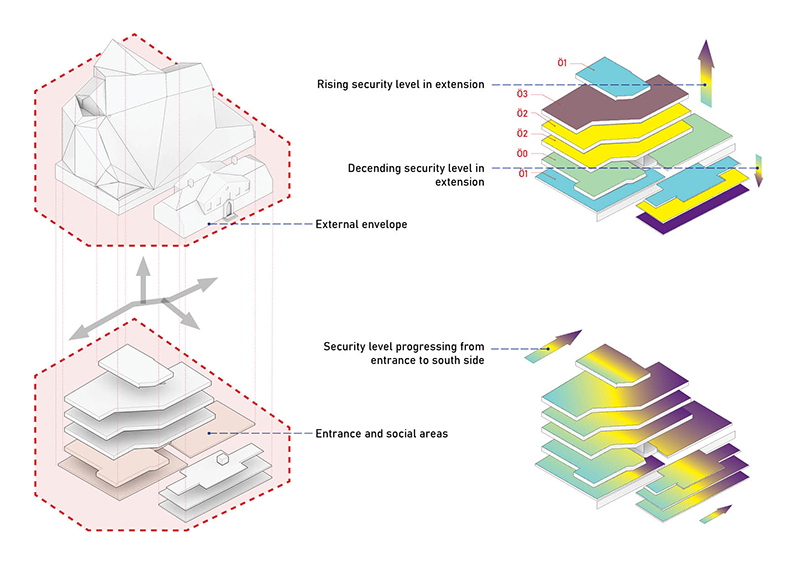

The brief called for a thoughtful connection between the new and old buildings with a resolved flexibility of internal layout that is adaptive to the needs of activities in both buildings. The proposal is striking in its simplicity. A central spine corridor with areas of public engagement and accidental encounters runs through the building from the new entrance. With increasing levels of security from front to rear, new to old, and ground floor upwards. Diagonally from the centre of the new building a corridor runs into the centre of the old Stjornarrad following the same principles.

With a more poetic architectural manoeuvre: rather than hide the building it in the built-up scenery of the back garden as the brief hinted at, we were able to turn the Ministry building into a constructive landscape, that through its spatial organisation bridges between the new public entrance and public space and highest governmental functions. Allowing the structure to act as both solid background and access in a single dramatic gesture.

Design

History

The Cabinet Building was built as a gaol between 1765 and 1770, built by local prison labour. Original drawings have not been preserved from history, but it is thought that the Danish Royal Architect, Georg David Anton, designed the building

The building was used as a prison until 1815. After that, it was re furbished and amended for a new and respectable role as the Kings Steward’s residence and later the Governor’s residence and office. The re-modelling was extensive before the King’s Steward Count Moltke moved there in 1819, including the front gable, but the footprint remained the same.

Prior to the executive moving to Reykjavik, it, along with the parliament (Althingi) were held regularly at Thingvellir to the east of the city (established 930 AD). The executive, judiciary and legislature powers were exercised in a volcanic ravine at Almannagja, with a tall cliff-face forming the backdrop and acoustic amplifier to the proceedings.

In 1904 with home rule, the building became the seat of the Cabinet and maintained that role until today. The cultural parameters of the building and the site look to be a core variable.

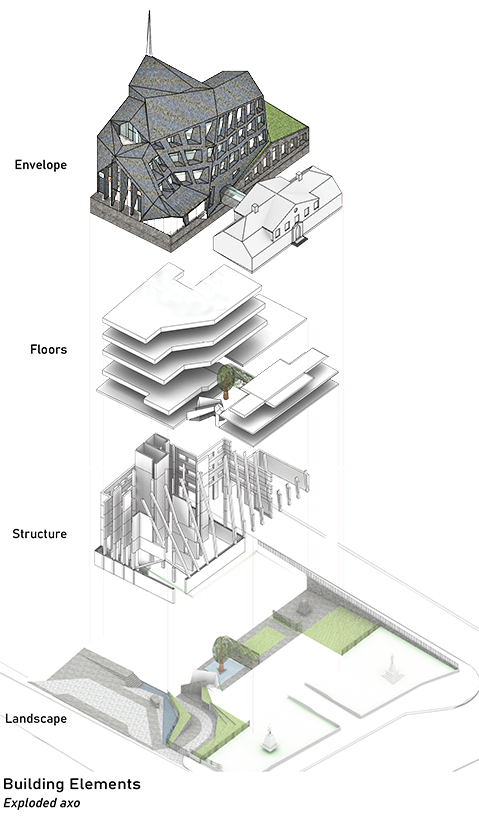

Proposal

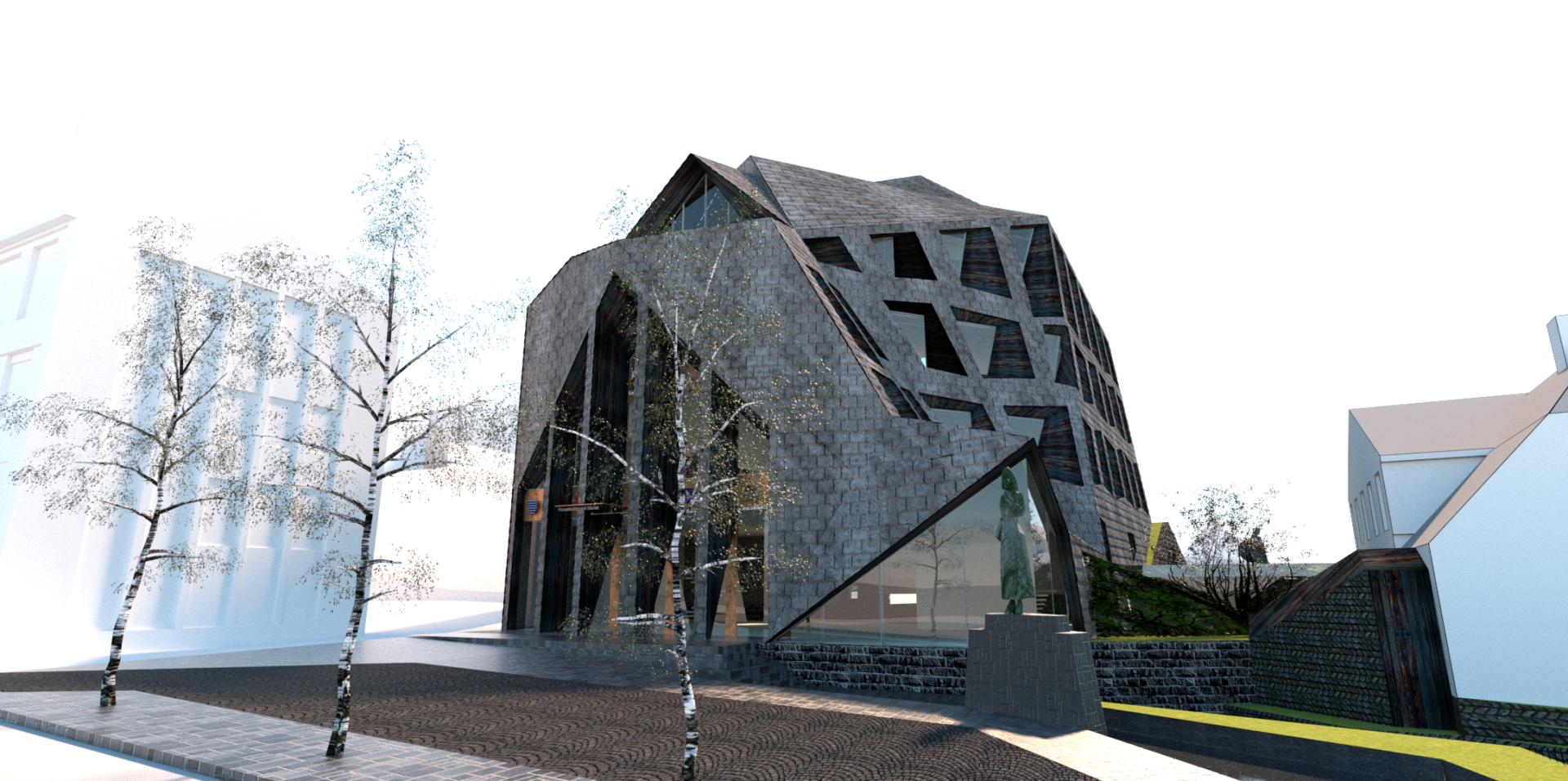

The white Stjornarrad building is a symbolic yet functional and cultural monument to the government of Iceland. The new building/extension needs to maintain this stature and support it, rather than hide it. Which is more likely to result in a Steisand effect as the new building is larger. Another option is to make it a pastiche seamless connection with similar architectural details. Which would compete with the original. Our parametric solution is to counteract the Stjornarrad architecture; by forming a new background to the building that increases it’s prominence. Civic architecture that succeed in expressing the needs and aspirations of its community, thus building a compelling argument against a mandated, unified architectural expression.

The building integrates the governmental facilities within a design defined by the existing building and urban environment of Reykjavik City Centre. The project maintains the detached character of the Stjornarrad building, allowing it to be read as separate element, while introducing a contemporary building that conveys the past, present and future evolution of the Ministry, government and city.

The Prime Ministry building complements the city´s cultural historical parametric context in its ongoing development. Its design weaves through the restricted site behind the protected Stjornarrad building, which it softly connects to and incorporates; while its stone and wood façade softly forms a natural background to the building’s context.

The geometric form of the façades adds a dramatic impact to the overall composition of the building. The form is derived from the design process resulting in abstracted forms that are meant to create a marriage of old and new cultural identities, through juxtaposition.

A building is the result of internal and external forces that act on spaces and forms of the building. The accommodation of these forces, or parameters, is achieved through a design progress. The process was historically analogue and based on (often) simplistic rules, but with advancing technologies we are able to measure and model these forces and manage complex systems that results from them.

Tectonic

Parametric Vernacular.

As a part of the use of emerging technologies in architecture, the design attempts to incorporate “cultural parametric” and “landscape” as variables in the design, creating a distinguishably Icelandic identity for the building. Modern architecture does not look favourably at identity; Identity sits within the prejudice of modern architects and their work far from culture and precedence.

Modernism is seen as mass-productive, utilitarian, and internationalist. It mostly ignores context, especially cultural, and as such, it can be placed in any context and still stay true to its design aims and its functional requirements. The design runs counter to these modernist principles, and makes an attempt at an example of contemporary architecture being transcribed as a part of Icelandic vernacular architecture, a cultural parametric design.

The Icelandic Althingi and Germanic parliaments in general were traditionally located in the landscape. Held at regular intervals with the participation of chieftains and the general public. With all powers executive, judiciary and legislature enacted at the events. This formed a core concept for the incorporation of cultural context and the solution to the relationship between the new and old building.

The external landscape is organized in the same way, and as an integral part of the building with every part of the landscape designed around specific functions. The arrangement of the new main entrance is well-resolved. The approach to driving and walking to the building is attractive and takes into account a role the building both as a ceremonial and public entrance, and as a place of public discourse and demonstration.

The landscaping of the plot and connection to the local area in considered from all angles, with consideration to the security of the building well considered, while still utilizing the landscape spaces as part of the internal functions. There spatial and cultural parametric methods for the New Building reflects a valuable architecture that is suitable for a respectful role the building and the historical importance of the place.

Materials

The building uses local materials to largest extent. Clad in granite stone shingles with shou-sugi ban burned timber used where the building mass is corbelled. Internally the material choice is focused on light and bright materials, countering the dark natural materials of the exterior.

Light is an important aspect in the design of a building, to conceptualizing light as a creator of space. Rather than just as a way to illuminate a space. A series of columns is a choice in light. The columns act as solids that frame the spaces of light.

The proposal recognises the specificity of the design process and the innovation that stems from understanding the local context

Any contemporary projects in the vein of cultural contextualism falls victim to being pastiche, or the prejudice of historicism or modernist internationalists, never progressing beyond models or drawings. It is up to the observer to determine if their judgment is justified, or if new landmarks like the Ministry Building could have captured a new regionalist architectural glory to rival that of the splendour and innovative attitude of vernacular architecture from the Red Square to American pueblos, Doge’s Palace Venice to Nidaros Cathedral. To find whether the use of cultural parametric design is a contextual solution to future architecture.